A Room of One's Own: On the Ways and Woes of Women

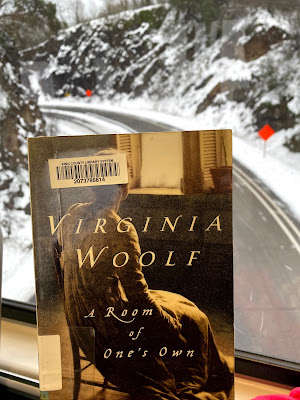

I recently read Virginia Woolf's A Room of One's Own, a timely read considering that I've temporarily moved to my mother's to study for the MCAT *because* it was nearly impossible for me to read a paragraph coherently at my grandmother's place (large families make for wonderful commotions). Having myself moved for the purpose of establishing a quiet space (literally a room of my own), it was hard not to read Woolf's essay through a symbolic lens. It was also hard to read this book without some level of emotional attachment owing largely, of course, to my gender.

Woolf writes brilliantly, as always - in fact, reading her work feels more like conversing easily with a close friend (albeit a one-sided conversation). When I first casually sat down to delve into this book, I had only a faint idea of its content. I was not prepared for the stimulating questions and perspectives that were posed relentlessly and, often times, rhetorically. The main idea(s) that the fictional character (whom we are permitted to call by "any name we please") explores is that of the financial bereavement of women, a historically standing status that persists in many parts of the world today, and the effect that this has on the role of women in fiction writing. It does not take long for the narrator to arrive at the conclusion that two things are required in order for any woman, or indeed any human yielding a mind and pen, to write fiction: a room of one's own and the financial means to support oneself. Now, I must remark upon the material and immaterial aspects of these two requirements. Firstly, and most importantly, is the financial means to host a space that one may call her own. This "space" can be considered as such in the physical sense of the word as well as the figurative. It is fairly easy to comprehend the physical aspect, so let us proceed to closely consider the figurative; space takes the form of time, silence, freedom (both financial and otherwise), and the physical parameters that establish these factors. What are the implications?

I am prompted now to raise a rhetorical question that the narrator posed at the start of the essay: what on God's green Earth were our mothers and foremothers doing all those years to leave us so financially disadvantaged? (remember to make the connection to writing fiction when I mention finances, for the former cannot possibly materialize without the latter). The narrator answers her own question: our mothers had neither the means nor the law endowed rights to obtain and accumulate wealth. Even if they wondrously had all of this, they had children to raise; first to sustain in their bellies and thereafter to rear and raise on God's green Earth. The insight here, then, is that women were not only deprived of the means to accumulate wealth, but that they were also, naturally, deprived of the time that it requires. They were deprived of the freedom and the quiet that writing requires as well. Is it a wonder that when we look to the genius minds that contributed to every imaginable field, we are confronted by the faces of men?

I have to state here, much to my discredit and your disbelief I'm sure, that I actually am not a feminist. But I am invested in all forms of truth. We all have roles to play, no doubt. This is a matter that has been exhausted already. Let us only acknowledge the full implications of these deprivations our mothers faced, and before the thoughts but they were clothed and happy and financially secure under their guardians/spouses and raising children, the great minds of the future comes to mind, I beg that you consider the various genius discoveries and contributions that women may have lent to society, had they been granted the means (both material and immaterial). Does it not evoke a sense of loss?

Now, to end this on a sentimental note, I implore you to read one of the most influential (in my opinion) passages in this book. It follows the narrator's reaction to discovering that she could finally quit the odd jobs she worked to support herself and write instead, thanks to the 500 pounds a year her aunt left her.

"But what still remains with me as a worse infliction than either was the poison of fear and bitterness which those days bred in me. To begin with, always to be doing work that one did not wish to do, and to do it like a slave, flattering and fawning, not always necessarily perhaps, but it seemed necessary and the stakes were too great to run risks and then the thought of that one gift which it was death to hide - a small one but dear to the possessor- perishing and with it myself, my soul - all this became like a rust eating away the bloom of the spring, destroying the tree at its heart.”

I can't really phrase the feeling that coursed through me as I read this - it spoke directly to me. It is as if my subconscious mind sat there alongside Woolf and penned those very words. Mary Oliver may also have been present considering that she said something along those lines:

"There is no other way work of artistic worth can be done. And the occasional success, to the striver, is worth everything. The most regretful people on earth are those who felt the call to creative work, who felt their own creative power restive and uprising, and gave it neither power nor time.”

Whether you be man or woman, I pray that we are granted the power, time, and space to harness our inner creative.

Comments

Post a Comment